What will be the right distribution key for future carbon revenues? That’s the question the Cooperative Committee considered on 14 May.

As you will recall, one of the main objectives of the Cooperative and its Cooperative Committee, made up of democratically elected representatives from each village (the majority of whom are women), is to draw up a key for distributing carbon revenues. It is certainly not up to arboRise to define how this income will be shared among the cooperative members. This choice must be made by those directly concerned, in accordance with local traditions and customs.

To prepare for this discussion, we asked the people most directly concerned, the land families, to think about the issue during visits to each village. 88% of all cooperative members took part in this consultation, and they agreed on the following consensus:

- Compliance with the cooperative’s rules by each member should be rewarded in proportion to the effort required to comply with each rule. For example, certain ‘costly’ rules (such as the installation of firewalls around the pitches) should be better rewarded than simple rules (such as the installation of marker tape around the pitches).

- Of course, those who do a great deal to foster the growth of trees on their plots should be rewarded, but the ‘undeserving’ should also be given a little, otherwise they risk leaving the project.

- The reward should (very clearly) be based on the result (the density and height of the trees on the land) and not for the effort required to achieve this result.

- External factors (infertility of the land, fires, etc.) should not be regarded as a fatality: it is the responsibility of the landowning family if it has chosen an unsuitable site or if its land has been affected by fires.

Then, this year, we hired the “measurers” to assess the quality of maintenance on the reforested plots and the growth of the trees. In this way, the performance of each plot is known to everyone.

On 14 May we provided the Cooperative Committee with a framework for reflection to help define the key to distributing carbon income. Please note that this is not a decision but a proposal that will be submitted to the land families for approval at the Cooperative’s General Meeting.

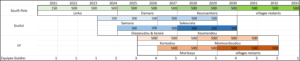

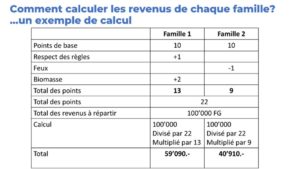

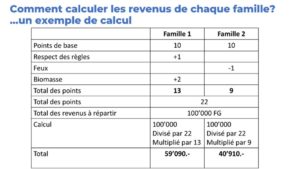

We began by recalling the results of the ‘tarpaulin exercise’ in 2024 in all the villages, and then by presenting the results of the measuring machines and satellite observations. Each dimension (fires, compliance with the rules, tree growth according to the results of the measuring machines and satellite images) is translated into a system of points per reforested plot, which, when added together, gives a result per plot-family, which can also be analysed by village, and so on.

Despite the relative complexity of calculating points and visualising them graphically, everyone understood the principle very well.

We then asked them to discuss and decide on two points:

- To what extent should the distribution key reward the deserving and penalise the ‘lazy’ (the adjective is from the participants!)? We explained to them that a too extreme distribution key could create major differences between the land-families and lead to conflicts. Following their deliberations, the members of the cooperative committee decided that the distribution key should lead to a small difference between the deserving and the less deserving. A wise decision

- How do you determine the share of carbon revenue allocated to the villages? Here too, we need to balance the desire of the land families to maximise their income, and on the other hand positive impact that an amount for community infrastructure will have (or on any jealous people in the villages). The Cooperative Committee proposes that the General Assembly should vote to allocate 10% to the villages.

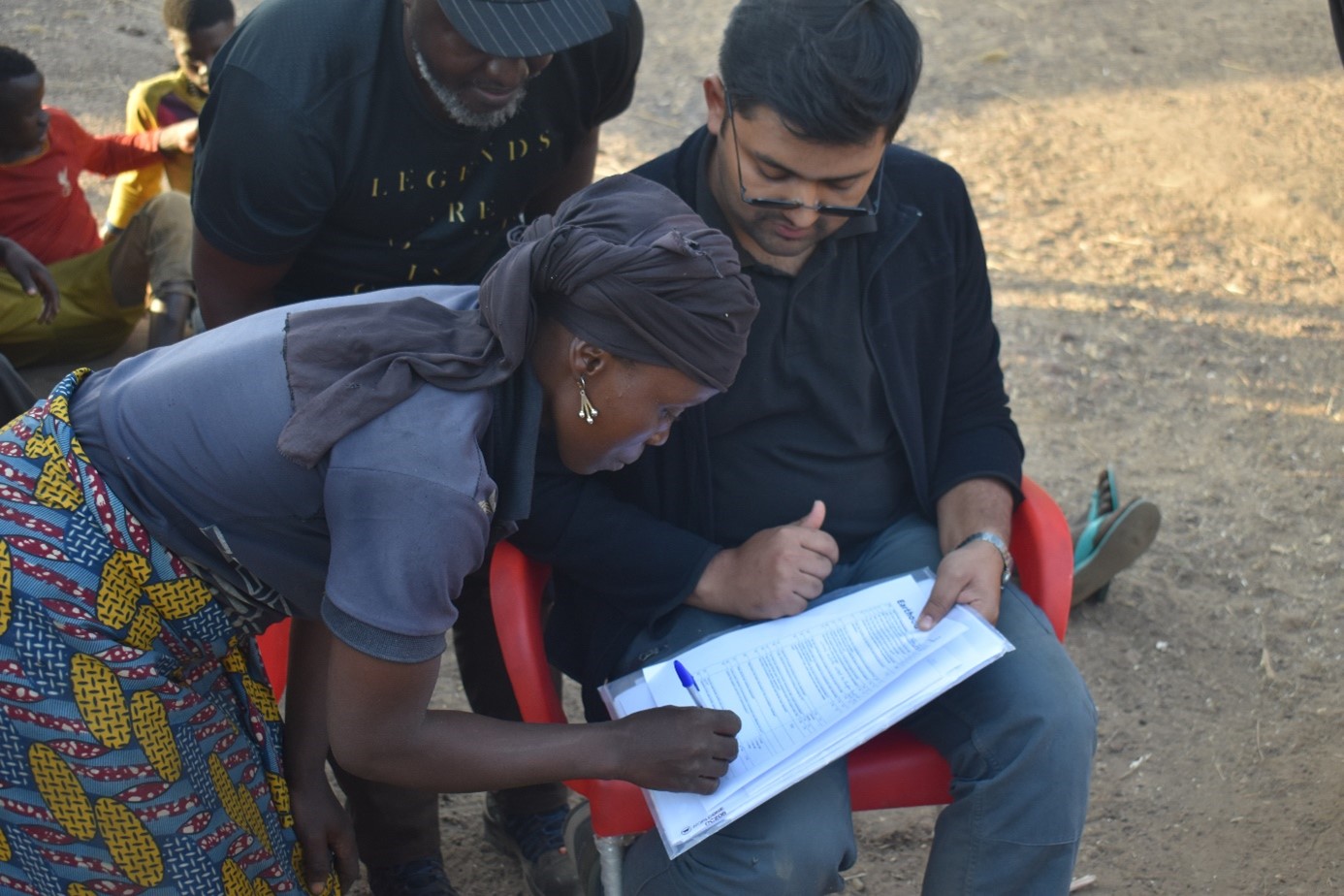

The members of the Comité Coopératifs first consult each other in groups, then report back to the plenary, and finally vote by raised hands.

This first exercise in reflection within the Comité Coopératif was a success. It shows that it is perfectly possible to delegate this kind of responsibility to the Cooperative’s bodies. The members are very aware of their responsibilities and a real dialogue is taking place (a deliberation, as recommended by the ethical supervision). This reflection will take place every year, before the Cooperative’s General Meeting. Over the course of those meetings, we will add elements for reflection (for example, we have not proposed a discussion on the weighting of the fire/rules/growth dimensions). In particular, we must ensure that the women on the Cooperative Committee take more airtime in the deliberations.